The curious incident of the Dáil in the night time

Last year the Government rushed through a contentious law on water. It’s now trying to fix the problem… by doing exactly the same thing.

Last year the Government rushed through a contentious law on water. It’s now trying to fix the problem… by doing exactly the same thing.

Note: This piece was edited at 7:45pm on Tuesday evening to reflect updated scheduling arrangements.

ON TUESDAY NIGHT last week, when Dáil Éireann traditionally sits until 9pm, it ended up working until a few minutes past 1am. On Thursday, when it usually adjourns for the week at 5:30pm, it sat until 10pm. On Friday, when it ordinarily doesn’t sit at all, it convened for four hours from 10am to 2pm.

And yet, on Wednesday, when it usually sits from 9:30am to 9pm, the Dáil ended up having to take 90 minutes off at teatime — because it hadn’t been assigned enough to do.

Manic working hours for TDs pre-Christmas are nothing new: there has always been a rush to get certain laws enacted before the New Year, but moving the Budget to October has meant there is an extra impetus to get certain financial measures put on the statute books before January 1.

That aside, however, there was one reason for the three unusually late sittings — and for the hour-and-a-half of empty time on Wednesday.

All three late sittings were needed to make progress on the Water Services Bill 2014, and on Wednesday, there was little appetite to debate a bill reforming water charges while there were tens of thousands of anti-water charges demonstrators hemming the building on both sides.

THIS WILL HAVE a funny knock-on effect on events inside Leinster House in the next couple of days. In keeping with the usual pre-Christmas rush, the Seanad will sitting all five days this week (its usual week is one full day and two half-days) — but even still, that won’t be enough to polish off the business of water charges. In fact, as the schedule is currently designed, Senators will likely be summoned back on Monday of Christmas week to apply the finishing touches.

This is because the government’s facing increased flak over how it organises its parliamentary business — and specifically its use of a contentious procedure known as the ‘guillotine’. This, in short, is where the government uses its parliamentary majority to shut down debate: scheduling a final vote to take place at a fixed time, irrespective of whether there’s been any debate on the various amendments tabled by the opposition.

Fine Gael and Labour claimed to have been elected in a ‘democratic revolution’, and in pre-election mode each promised to do away with some of the worst habits that Fianna Fáil had developed in the previous 14 years — the guillotine being one of them. But in the 31st Dáil, guillotines have been used to fast-track a decisive vote 31 times, including two bills triggering constitutional referendums. (In shambolic scenes, the guillotine fell so early on the Fiscal Compact that in concluding a debate on her own amendment, Catherine Murphy unwittingly filibustered herself by leaving insufficient time for a vote to be held.)

14 of those guillotines were applied in the Dáil in 2013, resulting in quite significant ire at the way the government had seemed to back-track on its prior commitments — five of them before Christmas, after a new suite of ‘Dáil reform’ measures had been implemented.

One of those bills was the Water Services (No.2) Act, which transferred ownership of the national water infrastructure to Irish Water — the handling of which proved so controversial that Fianna Fáil simply walked out of the chamber, unwilling to go through the motions of a pro forma debate with no prospect of the legislation being changed.

It is now quite evident that the mishandling of the Irish Water project has fundamentally changed the government’s mind on the use of guillotines. It appears now to be accepted that forcing legislation through the Houses without a full debate only denies the government the chance to listen to reasoned dissent. In 2014 there has only been one guillotine in the Dáil, on a bill to set up a Strategic Banking Corporation (which was passed unanimously, albeit with disquiet at the guillotine being applied while other amendments went unconsidered).

That record will be firmly put to the test this week, when the Seanad is due to begin considering the Water Services Bill on Thursday. The Dáil has effectively been given until 10pm on Wednesday night to finish the job, meaning roughly nine hours of debate.

Nine hours may not be enough. Currently the bill is in what’s known as ‘committee stage’ — the first point at which amendments are considered, and where every section of bill must be individually approved.

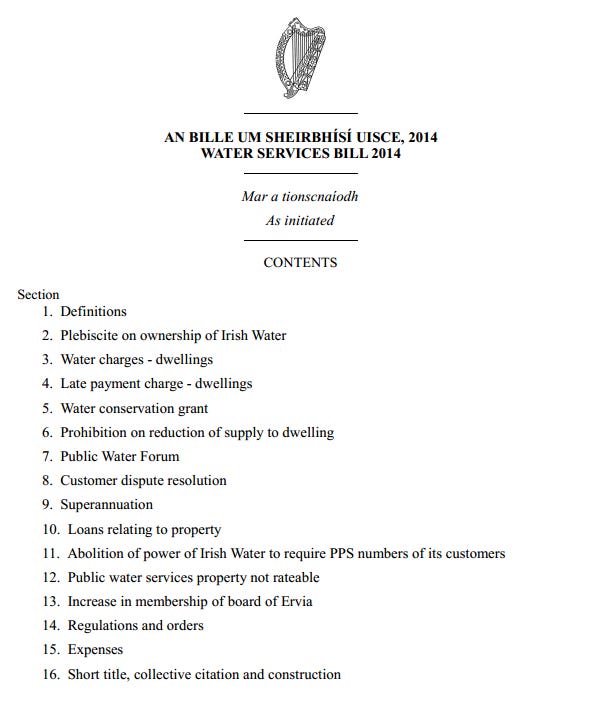

The Water Services Bill has 16 sections; currently only six have been processed, and 17 of the 46 proposed amendments are still to be considered. If every single amendment and section was voted on, that’s already over three hours lost.

It is entirely possible that the nine hours will not be enough to get the job done — meaning the government will either have to go back and embrace its old pal Madame Guillotine, or push the Seanad’s timeline back to Thursday or Friday.

And that’s where two new complicating factors come into play: our old friends John McNulty and the Constitution of Ireland.

Update: Since publication, the government has confirmed its plans to guillotine the bill — only the second guillotine in the Dáil this year. Debate on each section is being time-limited; if an amendment relating to that section hasn’t been disposed of when the time lapses, the amendment falls.

This has already brought about a Catherine Murphy-style situation.

45 minutes of debate were permitted on Section 8, which deals with the resolution of customer complaints. There was one amendment proposed, intending to allow Irish Water to consider complaints from people other than its own customers.

The debate continued for so long that the 45 minutes lapsed before there was time to vote on the very amendment that TDs had spent so long discussing.

ONE OF THE reasons why the government is under such pressure to get the Water Services Bill into law before January is because it’s fundamental to the revised scheme of water charges announced last month. If the new law isn’t active by New Year’s Day (or so the story goes) the ‘old’ regime will remain in place. So instead of bills being capped at €160 a year for single-adult homes, with the first bill arriving in April, the earlier system (capped at €178, arriving in January) will remain in place.

But leaving it so late to pass the legislation means the government is fighting against the clock. The constitution says the President, Michael D. Higgins, can only sign the law between five and seven days after it clears its passage through both Houses. This means that in order to have the law on the books before New Year’s Day, it effectively needs to be passed by Christmas.

And this is where Article 23.1.1° of the Constitution kicks in. It says that if the Seanad rejects any bill, or makes changes to a bill which the Dáil doesn’t accept, the Dáil can railroad its own version through anyway — but only 90 days after the Seanad’s finished its own business.

And in the case of the Water Services Bill, that’s pretty simple: if the Seanad rejects the Bill, the Dáil can only force it through by the end of March. If the Seanad amends it, the Dáil will either have to accept the amendments or accept the three-month delay — an intolerable delay given the apparent need to get the legislation on the books before January 1.

In the wake of the John McNulty affair, where a Seanad by-election became so botched that Fine Gael effectively abandoned it, the government is now in the minority in the Seanad: Fine Gael has 16 seats (excluding the Cathaoirleach, Paddy Burke, who can only vote to break a tie), and Labour 12 — some of whom regularly absent themselves when convenient.

The independent ranks include a dozen members — who in essence need to vote unanimously against the government in order to block something. For that reason, it’s not all that likely that the Bill as a whole will be roadblocked — as the government only needs a couple of swing voters to secure the passage of the bill, and at least a couple are likely to decide that the newer regime of water charges is a lesser evil than the old one.

But amendments are where things could get tricky. In the Dáil last week the government blocked amendments that many neutral observers would have seen as fairly harmless. Among them:

A clause which required the support of two-thirds of both the Dáil and Seanad, before a plebiscite could be held on the sale of Irish Water

A clause barring the government from spending public money to campaign for a Yes vote in any such plebiscite

A clause requiring the new ‘public water forum’ (intended as a vehicle for customers to air their concerns about Irish Water’s operations) to also include representatives from the trade unions of Irish Water workers

All three were opposed — and all three are among the possible amendments that could resurface when the Seanad gets as far as considering changes on Friday.

With the urgency on the Bill, the 90-day hold simply isn’t an option — and the Dáil will have to come back from its Christmas break (scheduled to begin on Thursday evening, for four weeks) to rubberstamp the Seanad’s changes.

In fact, both houses could end up having to come back. As I explained this morning, if the Dáil can only be reconvened after Christmas Day, then Michael D can only be asked to sign the bill after the New Year has already begun. The only way to bypass this is to recall the Seanad too, and ask it to pass a procedural motion urging the President to sign it earlier than otherwise expected.

Update: It’s now confirmed that the Seanad will sit on Monday to finalise its consideration of the Bill, and the Dáil will be on standby to sit on Tuesday and rubberstamp any changes the Seanad might demand.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how the government has found itself walking a tightrope — hoping it gets the assent of a house it doesn’t control, as it fixes one rushed-through law by rushing through another.