The Day Ireland Buried Its Ghosts

IT ENDED not with a whisper, but with a roar, so loud it was heard the world over.

IT ENDED not with a whisper, but with a roar, so loud it was heard the world over.

Everyone involved in the Yes campaign hoped their work would carry the campaign over the line. Everyone had suspected there was a solid public appetite for change; everyone feared that the votes of quieter, conservative rural Ireland might outweigh the live-and-let-live attitudes of city dwellers. Everyone hoped, hoped, hoped they had done enough to win. It didn’t have to be a landslide; a bare-bones majority would suffice. But nobody expected it to work out like this. Nobody expected a vote so visceral, so energised, so determined, so heartfelt.

Fine Gael backroom staff at their final campaign event on Thursday, keen to gleam predictions from journalists, revealed small bets they had made with each other. One predicted a Yes vote of 53%. Nah, said another: it will be 51%. Another, more confident, asserted 55%.

Throughout Friday — polling day — staff at The Irish Times and pollsters Ipsos MRBI watched their exit poll figures trickle in with almost total incredulity. Staff were assigned to follow turnout updates on Twitter, simply to corroborate the astonishing news unfolding before them. They had never intended to reveal the result immediately after polls had closed — but when the figures were added up, and the final prediction reached, the genie could not be kept in the bottle. At a minute past ten, the result: 68%.

Out in Montrose, where RTÉ had planned for its opinion poll only to be released at 11:30pm, David McCullagh playfully told others backstage at The Late Late Show that their poll had produced a different figure — and waited a moment before revealing to them that, in fact, it made Yes even higher. 69%.

The Eighth Amendment to the Irish constitution had not just been rescinded; it had been torn to shreds — and with it, any last belief that Ireland is a fundamentally conservative country. In the space of four years it had passed one of the world’s most liberal laws on transgender rights, become the first country worldwide to legalise gay marriage at the ballot box, elected a gay mixed-race Taoiseach without batting an eyelid, and now adopted a permissive abortion law in line with European norms.

Ireland may still be wedded to its traditions — where people tick the ‘Catholic’ census box by habit, but fill churches only on Christmas Eve and for secular friends’ weddings; where on the second Sunday of every May we threaten to pull out of the Eurovision, and eleven months later fret about the cost of inevitably winning it— but it is no longer bound by them.

Ireland is traditionalist, but no longer conservative.

VOLUNTEERS and campaigners filing into the vast exhibition space of the RDS’ Simmonscourt Hall did not expect to be in a position like this. They had knocked on the capital’s doors and were confident of solid support. Their fear was that the No vote, inevitably, would catch up in other areas.

Having expected the morning to be ravaged with tension, the campaigners were simply stunned into disbelieving silence. And so they moved; hundreds of volunteers in green Together4Yes hi-vis jackets, ready to watch the votes being counted so they could vouch for themselves. A smaller crowd of opponents, whose hi-vis jackets matched the pink of LoveBoth, stood beside them, tallying the ballots with duty but without hope. Their main spokesperson, Cora Sherlock, stayed for an hour but left to fulfil media commitments elsewhere and did not venture back.

The tally sheets were delivered to a team at the back of the hall, to be aggregated into overall totals and for box-by-box breakdowns to be etched into unofficial electoral history. Over the heads of that team, stuck to the RDS wall, was the picture of the woman who, perhaps more than any other, had brought Ireland to this point.

There, on the wall, was Savita.

SAVITA HALAPPANAVAR’S story had changed everything. That iconic image, of a smiling 31-year-old dentist in her finest Indian dress, had been burnt into the public mind. Her tragic story proved that the Eighth Amendment didn’t just affect crisis or unwanted pregnancies, but also planned pregnancies that were healthy until they weren’t.

Yes, her formal cause of death was the mismanagement of sepsis, but the chance of catching a fatal infection in the first place would have been far lower had she not been left waiting for a miscarriage to run its course. She lay on that hospital bed for two days, her membranes ruptured, her doctors unable to act because her foetus had a heartbeat and her own life was not (yet) at risk. The resulting sepsis killed Savita Halappanavar, who died four days after the daughter she so desperately wanted.

She wasn’t the only hard case, of course. We’d had the case of Amanda Mellet, who couldn’t end an unviable pregnancy in Ireland; who couldn’t afford to stay the night in Liverpool; who wasn’t given counselling in her home country, who unexpectedly received her child’s ashes by courier.

We had ‘P’, a brain-dead woman with her skull open and her decaying brain exposed; whose nurses put makeup on her so as not to upset her visiting children; kept alive because doctors didn’t know if they could withdraw life support while she was also 15 weeks pregnant.

We had ‘C’, a cancer patient who suffered a botched abortion in the UK after being unsure if further cancer treatment could harm her baby. We had an earlier ‘C’, a teenage rape victim brought to England for an abortion by the State without the knowledge she would lose her child — another victim without a choice.

We had one ‘D’ who lost one twin and was destined to lose another, but who could not end her pregnancy in her home country. We had another D, a teenager in State care and a foetus with anencephaly; who wanted to exercise her constitutional right to travel to England for abortion and was intimidated by the HSE with a restraining order that didn’t exist.

And, starting it all, we had a 14-year-old lumbered with her rapist’s child and the pseudonym ‘X’. Perhaps many, placing an X in the box marked ‘Tá’, had done so thinking of the girl with the same name. Perhaps that girl, who would now be a woman of 40, was one of them.

But Savita’s case hit home more than most, perhaps because we knew her name, her face, and her date of death.

It was perhaps little surprise that RTÉ’s exit poll said, despite the months of rigorous campaigning, three-quarters of voters had made their minds up five years ago or more.

AMONG THOSE watching the count in the RDS was Shampa Lahiri, who felt the tragedy of Savita more personally than most. Australian born to Indian parents and married to a Dubliner, Lahiri had become a naturalised Irish citizen and had cast her first vote mar saoránach Éireannach in favour of Repeal.

She came to watch the count in a sari with gold trim and a Bindi on her forehead — a visual tribute to her fellow Indian who was no longer around — and spoke fiercely, forcefully, assertively, emotionally.

“Every migrant comes here in search of better lives,” she said in a lilting Australian accent.

We come here to work hard, and to have better access to opportunities than in the country of origin that we come from. We don’t come here expecting to die in a public hospital, under the care of trained professionals.

Regardless of which side of the debate were you on this referendum, everybody has to recognise that what happened to Savita Halappanavar should never have happened.

SHORTLY AFTERWARD came Dr Peter Boylan, a former master of the National Maternity Hospital, a man recently retired from a lifetime of bringing babies into the world. Boylan’s vocal support for a Yes vote had made him a hate figure for some No voters — far from loving babies, he was now a man creating fictional medical quandries because he wanted to kill them — but that was in the past now.

He arrived in the RDS to a hero’s welcome and a media scrum. Did he have sympathy for those who opposed him? “A lot of those couples choose to continue on with their pregnancy, and they are looked after, with all of the compassion and care that we weren’t able to give to women who had to travel — who chose not to go through to the end of the pregnancy, but to deliver their much loved babies, and kept mementoes and so on. So of course you have sympathy for people who voted No — they voted No out of genuine concerns.”

There were three other media scrums. The first was for Mary Lou McDonald, whose recent ascent into the shoes of Gerry Adams had already caught international headlines, and whose profile now attracted the attention of every foreign reporter in the building. Her own constituency had voted 76% Yes, but she freely admitted she didn’t expect such a margin of victory nationwide. The people had led the politicians on this subject, she said, but that probably wasn’t much harm.

The second was for an unlikely hero, Simon Harris, who at 25 said he would have “grave difficulty” supporting a new abortion law, and at 31 had led a referendum to secure one. “Under the Eighth Amendment,” he announced, “the only thing we could say to women [in crisis pregnancy] was take a flight, or take a boat. Now the country is saying, No: take our hand.”

Kate O’Connell, a vocally pro-choice party colleague, shed a quiet tear standing beside him. So did one of the many journalists in the scrum.

But the biggest scrum, and the most joyful cheer, came for the three co-chairs of Together For Yes: Ailbhe Smyth, Orla O’Connor and Gráinne Griffin. Smyth had been agitating for this change for 35 years, and was overcome. The crowd was so large, and her voice so thin, that she could barely be heard now.

That now seemed unimportant. Her message, evidently, had been heard.

WITH THE EXIT polls proven correct by the tallies, there was little more to do at the RDS and so the journalists slowly headed towards Dublin Castle for the national result. But first, a detour.

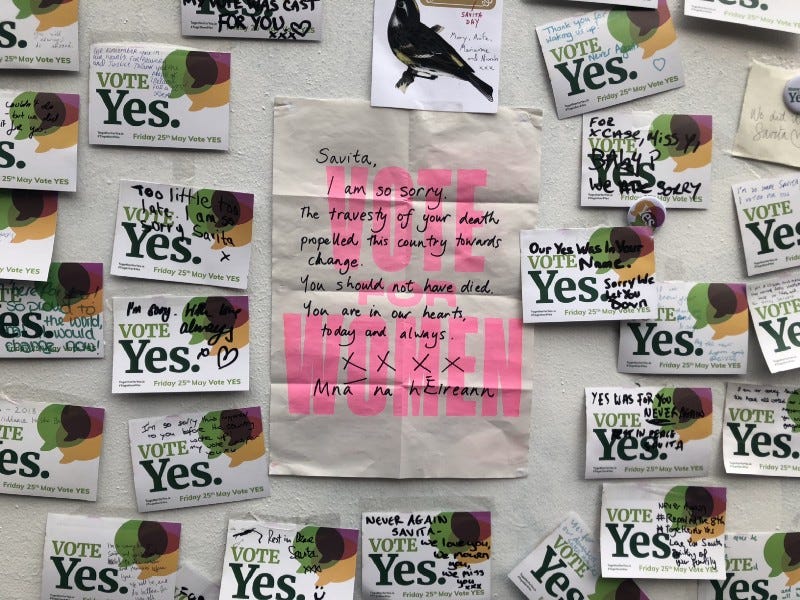

A few days before polling, a hoarding on a vacant site in Dublin’s artsy Portobello district had been painted with the face of Savita and a simple word, ‘YES’. It had become an immediate rallying point, and on Friday some voters laid flowers in her memory, while some others wrote messages on Together For Yes postcards and stuck them on the blank space beside her.

As the result became clear, voters who wanted to celebrate went straight to Dublin Castle; those who wanted to reflect, went to Savita. The few postcards on the wall had become a few hundred, all of them with messages of sorrow and sympathy that it had taken this woman’s harrowing death to trigger a critical mass for change.

One simply said: ‘My Yes was for you.’

IN DUBLIN CASTLE, an impromptu party had broken out. A choir group, Voices for Change, were singing pop classics with the lyrics changed to reflect the referendum (as if Journey had written ‘Don’t Stop Repealing’, or Tracy Chapman’s hit was ‘Talking ‘Bout A Referendum’). Another group, Angels for Repeal — a group of people literally dressed as angels, not all of them women — were dancing along with abandon.

Political leaders arrived, each welcomed with open arms. Peter Boylan arrived and had his name chanted by the thousands present. So too did Ailbhe Smyth, with a raucous cheer and the chanting of her name when she materialised on the stage.

Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin was warmly welcomed, with crowds appreciating his internal party trouble for backing Yes when most of his colleagues didn’t. Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O’Neill drew wild approval when holding a sign that said, ‘The North is Next’, leaving it open to interpretation as to whether they meant abortion or constitution. Catherine McGuinness, Ireland’s answer to Ruth Bader Ginsberg, seemed incredulous that she might personally be received so happily.

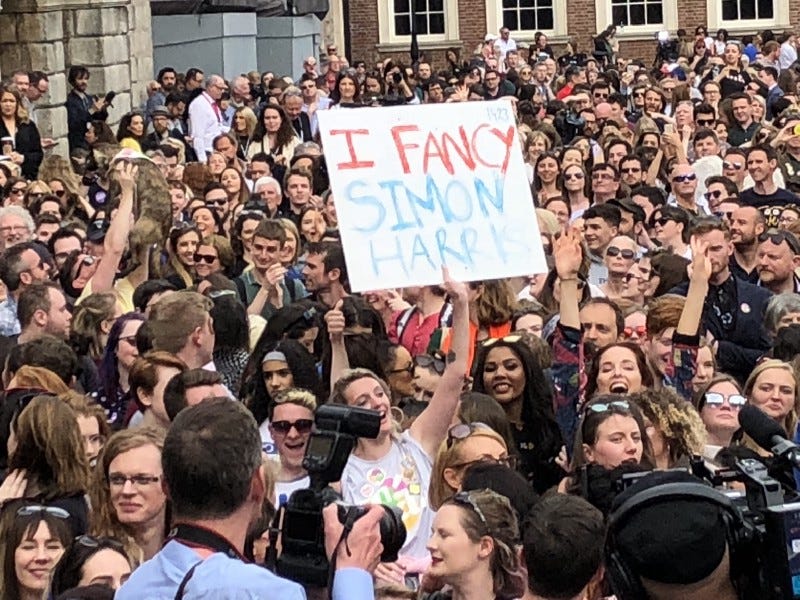

Simon Harris arrived to such a raucous reception that one female fan, holding a speech-bubble ‘Yes’ sign, had put a message in lipstick on the other side: ‘I fancy Simon Harris’. He also appeared on stage, alongside Leo Varadkar, Regina Doherty (in a Repeal t-shirt), Helen McEntee, Fine Gael’s campaign director Josepha Madigan, and Catherine Noone, the Fine Gael senator who chaired the vital Oireachtas committee which midwifed the ‘radical’ recommendations of the Citizens Assembly into Leinster House.

But Harris was the star of the show. The crowd chanted ‘speech’ and so he delivered one, without a PA system or a microphone to carry it, with the hundreds present hushed to silence. Slowly making his way back through the crowd afterwards, snailing through a series of selfies, Harris sought out the holder of the ‘I fancy Simon Harris’ sign and politely kissed her on the cheek.

While some left-wing TDs like Brid Smith and Ruth Coppinger were on the stage, neither took a ‘curtain call’ in the way that others hand.

Other TDs, like Clare Daly, Mick Wallace and Joan Collins — who backed new laws on abortion when it was far from fashionable — were nowhere to be seen.

JUST AFTER 5pm in the afternoon, word began to circulate that the final announcement was likely to be made at 5:30pm. The stage therefore began to empty, as campaign leaders went inside to the Hibernian Conference Centre, in the basement bowels of Dublin Castle’s south-east corner, to hear the final result being announced. The same privilege was not afforded to the citizens in the crowd, left outside with no big screen and only an improvised audio feed for posterity. Yet they were heard, their cheers echoing through the room as the returning officer announced the totals.

2.15 million votes had been cast — more than any other referendum in Irish history. 1.43 million, 66.4 per cent, were for Yes. Of the 40 constituencies in Ireland, only Donegal had voted No, and then only by a small margin.

Back outside, then, to hear the Taoiseach issue a formal statement to a global audience and a modest media turnout.

“I believe we have voted for the next generation,” Leo Varadkar announced to us. “We have voted to look reality in the eye and we did not blink.

I believe today will be remembered as the day we embraced our responsibilities as citizens and as a country: the day Ireland stepped out from under the last of our shadows and into the light; the day we came of age as a country; the day we took our place among the nations of the world. Today, we have a modern constitution for a modern people.

He left, without questions, before we could ask what that meant.

BY THE TIME we were back in the courtyard of Dublin Castle, the crowd had begun to dissolve.

A small part of that crowd had made the twenty-minute walk to Portobello, to Savita’s mural, where nobody spoke above a whisper. The pile of flowers was bigger than a few hours ago, while the wall of postcards had grown and grown.

Evidently, at one point mid-afternoon, the pile of blank postcards had run out; one person improvised, writing their message on a ‘Votes for Women’ poster left over from the celebrations to mark the centenary of women’s suffrage.

“Savita, I am so sorry,” it read.

“The travesty of your death propelled this country towards change. You should not have died. You are in our hearts, today and always.”

It was signed, ‘Mná na hÉireann’. The women of Ireland had sent their message.

More postcards had arrived later, and more and more people left their messages, saying sorry to a 31-year-old immigrant they had never met. Their tokens of support, sympathy, solidarity, now covered almost all of the wall and crept to cover Savita’s face. It was almost as if, with her mission accomplished, there was no wish to remain haunted by her.

The people of Ireland had paid their best possible tribute to Savita Halappanavar: they had allowed her to rest in peace.