Nine reflections on the opening day of Election 2024

Buckle up: we're going to be here a while.

43 constituencies. 174 seats. 580+ candidates, and up to 3.4 million eligible voters. 21 days to decide, five years to govern.

Let’s get started…

Campaigns matter. No, they really matter.

You can never know what issues will pop up on the trail that suddenly dominate the national conversation. The Fine Gael government was already wounded by the ‘Black and Tans commemoration’ controversy in the first week of January 2020, and no sooner had the election been called - on the back of a motion of no confidence in Simon Harris, remember! - then a homeless Eritrean asylum seeker was disfigured when his tent was mauled by machinery on the banks of the Grand Canal. That happened in the shadow of a poster of the then-Minister for Housing.

In 2016, meanwhile, the Regency Hotel shooting occurred on Day 3 of the campaign - prompting Gerry Adams, then the SF leader, to suggest that the non-jury Special Criminal Court could be disposed of, with prospective witnesses could simply be put into witness protection instead.

And don’t forget; in the 2020 exit poll, only 48% of voters said they’d made their minds up on how to vote before the campaign began. These things matter.

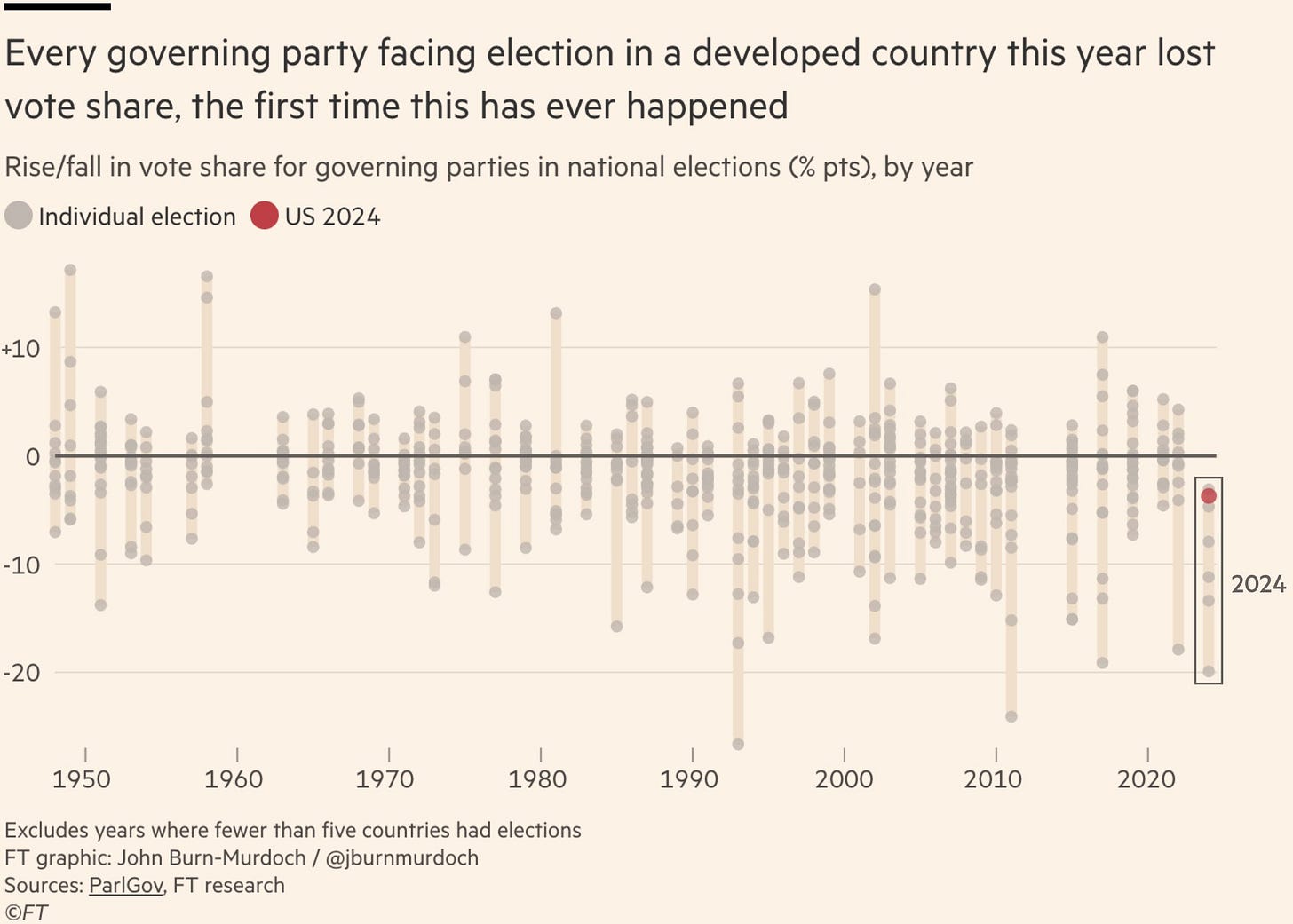

Incumbency is not A Good Thing in 2024

Every election is different, and Ireland’s electoral system is more nuanced than most, but 2024 - ‘the Year of Elections’ - has not been good to incumbent governments:

Granted, Ireland has three incumbent government parties, so it’s plausible that at least one of them could increase their share. But it’s far from a given, and they’re fighting against the global trends.

Fianna Fáil may accrue more transfers than in 2020

A forgotten aspect of 2020, overlooked in all the post-mortems about Sinn Féin’s astonishing surge, was that Fianna Fáil let seats behind. The epilogue from the 2020 edition of Newstalk’s ‘Calling It’ (hosted by myself alongside Ivan Yates - Seán Defoe is joining him for this year’s version - is an enlightening listen at a four-year remove.

So many of the final seats in various constituencies ought to have been claimed by Fianna Fáil, but their candidates fell short because they won disproportionately fewer transfers. That’s because confidence-and-supply was an electoral disaster - FF didn’t get much in transfers from any other opposition parties, whose supporters saw FF as being in government by proxy; nor did they get (many) transfers from Fine Gael, because that Rubicon was not yet crossed.

This time around, with the Chinese wall between FF and FG now finally smashed, Fianna Fáil will be more transfer attractive to supporters of FG. They might even get some help from the Greens, in as much as they’ll remain an electoral force.

Speaking of which, though…

How will the Green Party fare? And is rural pushback really an issue?

If you consumed your politics solely through the medium of soundbites from rural independent TDs, you’d think Eamon Ryan was the devil incarnate. And granted, the Green Party does not have the wind at its back this time in the same way that it did in 2020.

But: being hated by rural voters doesn’t necessarily put their current seats in peril. Eight of the outgoing 12 represent Dublin constituencies, where carbon tax is not the big vulnerability that it might be in other parts of the country. The other four TDs - Steven Matthews in Wicklow, Marc Ó Cathasaigh in Waterford, Brian Leddin in Limerick and Malcolm Noonan in Kilkenny - represent cities or quasi-cities. It’s inevitable that the smallest party in government will ship losses, and the increase in Sinn Féin and other left-wing candidates will mean fewer transfers falling the Greens’ way. But all isn’t lost.

How do the big two differentiate themselves?

I’ve no idea - and when it comes to the final TV debate, when the ‘big three’ parties of prospective Taoisigh are on stage against each other - Mary Lou McDonald will have the time of her life dropping the words ‘Tweedledum and Tweedledee’.

The disputes between the big two - which will be semi-manufactured and semi-genuine, given the possibility that the job of Taoiseach might not be as willingly rotated the next time - will be a theme.

It’s a long time since campaigns were so Presidential

Simon Harris will have run out of backing tracks for Instagram reels by the time all this is over - he’s barely in and out of a constituency before a bouncy video gets posted showcasing his flurry of handshakes.

But that’s a conscious (and logical) choice for Harris to pursue, when 18 of the 35 Fine Gael TDs elected in 2020 aren’t on the pitch this time. Given the loss of so many ‘safe seat’ incumbents, the logical pursuit for FG is to try and make the election less about the candidate and more about the brand. There are parallels with the UK’s system: does it really matter who your local Labour or Tory candidate is, when all you care about is whether it’s Boris or Corbyn, Starmer or Sunak? Reducing your local candidates to proxies for their party leader is a sensible thing to do when you’re losing incumbents and your leader is popular.

Fine Gael aren’t the only ones leaning so vigorously into this though. A cursory drive around Dublin as the first posters went up, show a higher-than-usual proportion of party leaders’ faces alongside those of their party candidates. Harris seems to be on a whole heap of FG posters. Micheál Martin has been significantly more popular than his party for a long time (so much so that many FF frontbenchers have long resented how centralised the party is managed). Mary Lou McDonald is appearing on other candidates’ posters.

Even Holly Cairns is on posters for SocDems’ colleagues - which is particularly striking given she may not be a full part of this campaign, and given her own seat is not nailed down (she polled 6th in a three-seater last time). Without wishing to put a hex on her campaign: in hindsight it might look a bit like ‘Jo Swinson For Prime Minister.’ The Liberal Democrats’ leader in 2019 wanted the title of PM, but lost the title of MP.

Fianna Fáil did a bit of this in 2007 (the party slogan was literally ‘Bertie’s Team’) - the last juice to be squeezed out of that particular fruit - but beyond that you’d have to go back to the 1980s, or even the 1970s (‘Bring Back Jack’, anyone?) to find a culture so centrally presidential as the one we’re in now.

Incumbency Is Not What It Used To Be

Johnny Mythen of Sinn Féin lost his council seat in Enniscorthy in 2019, winning 818 votes - only half a quota. In the general election eight months later he got 18.717 - one and a half quotas - in Wexford and could probably have brought home a running mate with him.

Had there been a second Sinn Féin candidate, one or other of FF or FG would have dropped a seat; incumbents Paul Kehoe (FG) or James Browne (FF) would have fallen.

Both of those men defeated Michael D’Arcy (FG) who was an outgoing TD; both also ended up ahead of Malcolm Byrne (FF) who won the by-election in November 2019 but lost the seat again eleven weeks later. The only shorter-serving TD in Irish history literally died in office.

Holding a seat does not give the advantage it used to.

Where’s all the money going to come from?

We can expect much of this year’s campaign to have an auction-y feel to it. That’s fair enough: the country’s literally never had so much money.

Except: yeah, yer man.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House in January - likely with a House and Senate both controlled by a party which has now been comprehensively recast in his own image - means a likely cut in U.S. corporate tax rates, from 21% down to match Ireland’s 15%. Moreover, having not quite finished the job in his first term, and now knowing how exactly to wield the levers of power, he’ll likely start being more aggressive in trying to repatriate American firms who have declared Ireland some kind of offshore headquarters.

There won’t be an exodus of tech firms - aside from the low taxes we also have access to the EU’s single market, a well-educated workforce, and a good command of English - but merely shifting headquarters, or moving intellectual property out of Ireland, would be bad news. The top three contributors to corporation tax are, alone, responsible for about €10 billion of Ireland’s annual income. That’s about a third of all of Ireland’s corporate tax revenue, and about one-tenth of the government’s entire income. Take that away, and Ireland’s healthy surpluses literally disappear overnight.

On the flip side, Trump’s plans to levy a flat-rate 20% tariff on all imports (which is hard to square with America seeking trade deals with the EU) could result in a domestic depression in the U.S., given that America cannot readily substitute all of its imports with home-made alternatives. As the saying goes: when America sneezes, the world catches a cold. We cannot expect the money to keep on rolling.

Be prepared for longer counts

More candidates simply means taking more time to declare the final results. Those of you who watched the European elections counts in June will recall how, even if many candidates don’t have a sniff of getting elected, they’ll still have to be eliminated and their votes transferred, as with anyone else.

And there will be more candidates in 2024 than ever before. As it stands, six parties - FF, FG, SF, the Greens, Aontú and PBP-Solidarity - are likely to have candidates in every single one of the 43 constituencies. So too might the alliance of right-wing nationalists, who have learned from June and are now avoiding the prospect of splitting a finite vote between too many candidates.

There are more constituencies this time, which means fewer five-seaters… but the five-seaters that survived could yield marathon counts. Prepare yourselves.

(And get ready for some interesting spreadsheet initiatives… more of which anon…)

I look forward to many spreadsheets